Introduction

Go has been around since 2012, developers are starting to recognize how powerful it is and are slowly transitioning to developing their projects with Go. It’s becoming extremely popular in “modern enterprises” for many reasons, one of which is that it’s really simple to learn and use yet produces cleaner code! especially if you have a background in C++. But that’s not the only reason many developers are rooting for it. Other reasons include how fast it is to compile and execute, how it boosts maintainability and readability of the code by providing its own preset of code style standards and most importantly, the way it handles concurrency!

Now let’s focus on what makes go really special, the way go handles concurrency allows multi-threaded apps to work blazing fast! But before digging deeper into how it does that, let’s take a step backward and explain what concurrency is and what is a thread?

Feel free to skip to the goroutines part if you already know about concurrency, parallelism and threads.

Concurrency & Parallelism

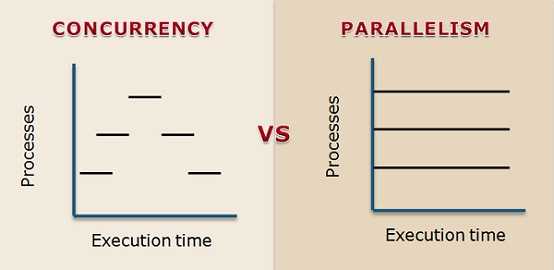

Well wikipedia defines concurrency as… Just kidding, if you’ve never heard of concurrency then wikipedia’s definition of it would rather throw you off. In a nutshel, concurrency allows programs to deal with multiple things at the same time. It’s also important to mention that it doesn’t necessary mean to actually process multiple tasks at the same time on the CPU level. But it deals with them at once nevertheless and let’s now explain what that means, the following might not be 100% true for each and every use-case because some CPU’s or operating systems operate in various ways internally. I’ll also ignore some technical details such as threads for now to make it simpler to understand (I’ll be using the word “task” instead of “thread”) and explain it later on. But the overall process shouldn’t differ much.

Concurrency on Single-Core CPU’s

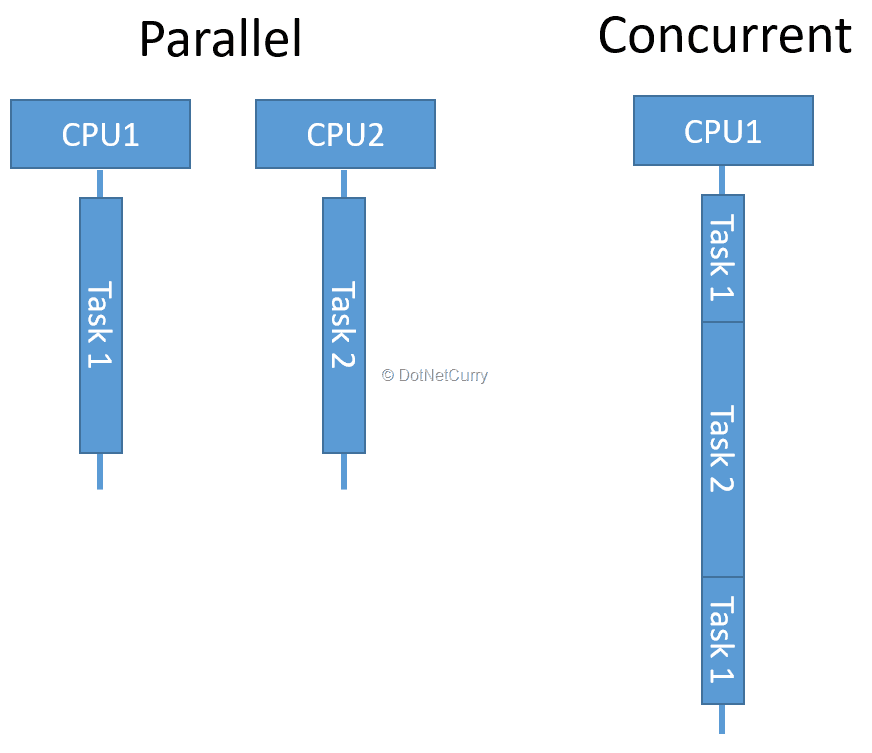

CPU’s either have a single core or multiple cores, for the sake of simplicity let’s first explain how concurrency work on a single core CPU, then understanding how multipe core CPU’s work should be a cakewalk. On a single core CPU. the single core (processor) might trick you to think that it’s executing multiple tasks at once, when in fact what happens is that the task execution in the processor is overlapping, meaning that each task is given a time window on the processor to run on, then it would be replaced with another task to be executed on that processor.

In other words, if we have task “A”, “B” The processor might first assign task “A” 5 microseconds to execute on it, then even though task A needs more time to finish, it tells task “B” to take over and do the computation it needs for let’s say another 5 microseconds. And finally when task “B” is done executing, task “A” can start processing again for another 5 microseconds. Since it’s getting executed in almost no time (microseconds), for you as a human you wouldn’t even notice those processes have been overlapping or got executed one after the other. They would appear to you on the screen as if they were running at the same exact time. When in fact the processor has been running different tasks at different time windows to achieve Concurrency. Which is as we described it earlier, the way the processor allows tasks to share it in order to process the computations they need. Concurrency on the kernel level is the responsibility of the OS (operating system) scheduler, which is a program that the processor relies on to achieve all of this.

Concurrency & Parallelism on Multiple-Core CPU’s

Now what about mutliple core CPU’s? Well here comes Parallelism. the CPU can now run multiple tasks at the same exact time thanks to the multiple-core (multiple processors) infrastructure it has! Which means it can let multiple tasks run at once on different processors. Now you might be wondering “Would that mean we don’t need concurrency anymore?” and the answer is No. This doesn’t mean concurrency is “no more”. Concurrency and Parallelism are two completely different things. Concurrency would probably also exist on multiple-core CPUs to make them even more efficient. And now that you understand how concurrency works on a single-core CPU. Just imagine the same thing being done on each and every processor. That’s because every processor/core runs an instance of the OS scheduler we talked about earlier. Which allows for concurrency on the processor. Here are some images that might explain this even better, but don’t get confused with how concurrency is being demonstrated as if it’s running on only one processor and the processes are sharing the processor. Just imagine it doing the same thing demonstrated on the following images for every processor that exists on the CPU.

Programming language have different ways of handling concurrency. That’s if it’s supported by the language in the first place. But that’s not our topic, if you’re interested in learning more about what concurrency is I’d really suggest getting the book “Operating System Concepts” by Abraham Silberschatz, Peter Baer Galvin, and Greg Gagne. It explains all of these concepts along with other interesting stuff.

What is a Thread?

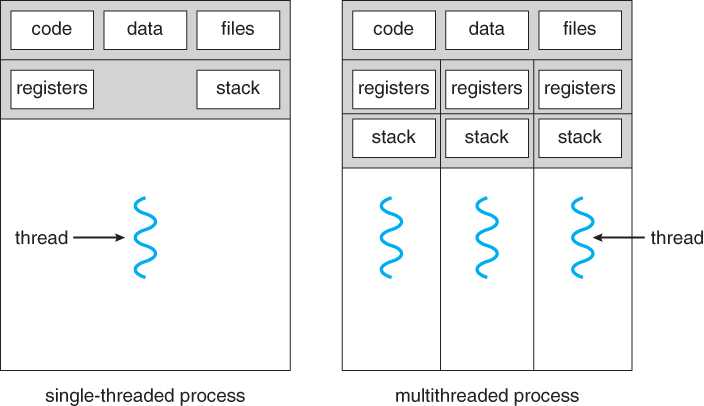

In the last section we were talking about how tasks are sharing the processors in order to run some computations. Well the truth is, tasks don’t even have access to the processors or use them directly. They make use of Threads, which have access to the processors.

The best definition of a thread I could find was this by pwnall on stackoverflow:

A thread is an execution context, which is all the information a CPU needs to execute a stream of instructions.

Suppose you’re reading a book, and you want to take a break right now, but you want to be able to come back and resume reading from the exact point where you stopped. One way to achieve that is by jotting down the page number, line number, and word number. So your execution context for reading a book is these 3 numbers.

If you have a roommate, and she’s using the same technique, she can take the book while you’re not using it, and resume reading from where she stopped. Then you can take it back, and resume it from where you were.

Threads work in the same way. A CPU is giving you the illusion that it’s doing multiple computations at the same time. It does that by spending a bit of time on each computation. It can do that because it has an execution context for each computation. Just like you can share a book with your friend, many tasks can share a CPU.

On a more technical level, an execution context (therefore a thread) consists of the values of the CPU’s registers.

Each thread indeed has its own independant context, you can even think of a multi-threaded program as separate programs that together compose an even larger one. Here is a diagram that might help you visualize this:

Single-threaded process can only run a single task at once, while multi-threaded process can run an N number of tasks simultaneously.

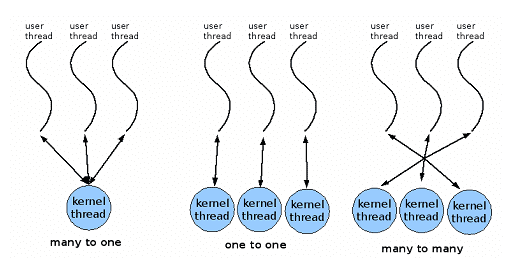

Threads are created and managed in different ways or models so to speak. One-to-one, many-to-one and many-to-many models. Which are basically mappings between user (application-level) threads and kernel (OS level) threads.

Goroutines: Go’s way of dealing with Concurrency

One of the reasons developers like Go is how easy and efficient it is to implement Concurrency with it. It’s an inherent part of the language. Goroutines utilizes a concept that has been around for a while called “coroutines” which essentially means multiplexing a set of independently executing functions “coroutines” which are running on the user level, onto a set of actual threads on the OS level. That’s what makes goroutines incredibly efficient. You might be wondering why? Because when a coroutine blocks —some processes cause threads to block for many reasons—, such as by calling a blocking system call (e.g. reading an input from the user), the run-time automatically moves other coroutines queued behind the blocking coroutine on the same operating system thread to a different, runnable thread so they won’t be blocked. This might be a bit confusing to digest at first, so let’s demonstrate it with an example:

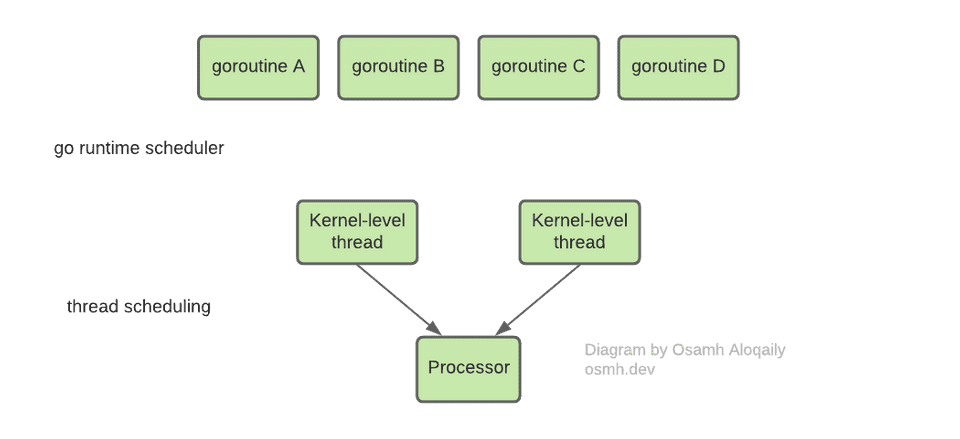

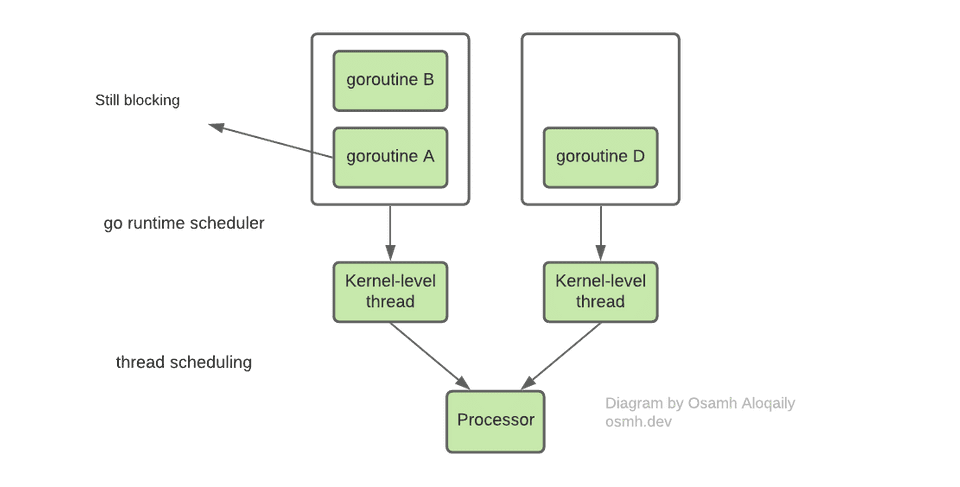

- First let’s assume we have 4 goroutines that need to be multiplexed onto kernel-level threads in order to get executed. Let’s also assume we only need 2 kernel-level threads. And we have a single processor.

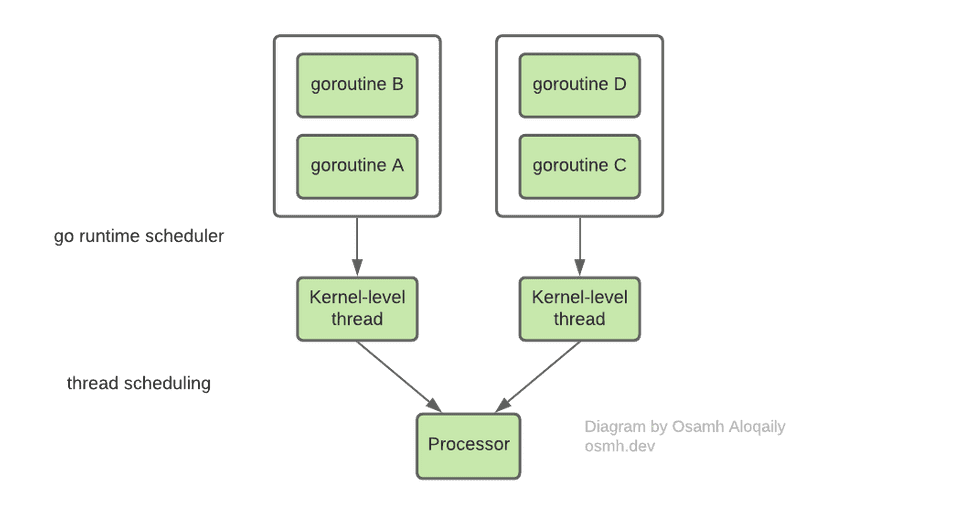

- Now let’s assume go’s run-time scheduler decided to mutiplex the goroutines onto the threads like so (for any reason). Goroutine A & B would run using the kernel thread on the left, goroutines B & C would run using the one on the right. Let’s also assume goroutines will run respectively, starting from the goroutines placed on the bottom of the pool of goroutines, demonstrated with the border surrounding them.

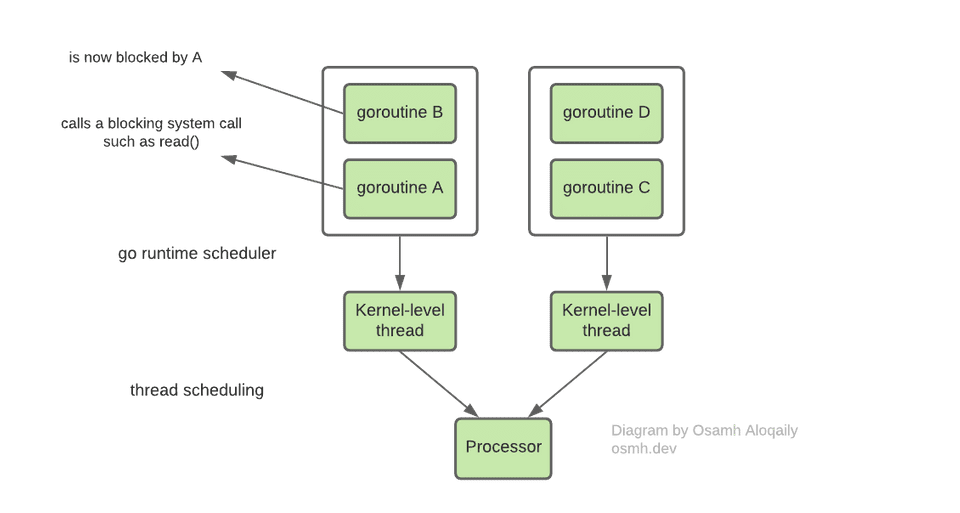

- Goroutines started running. But wait.. “A” has called a blocking system call (e.g. read() statement) Now goroutine A is blocking and goroutine B is blocked.

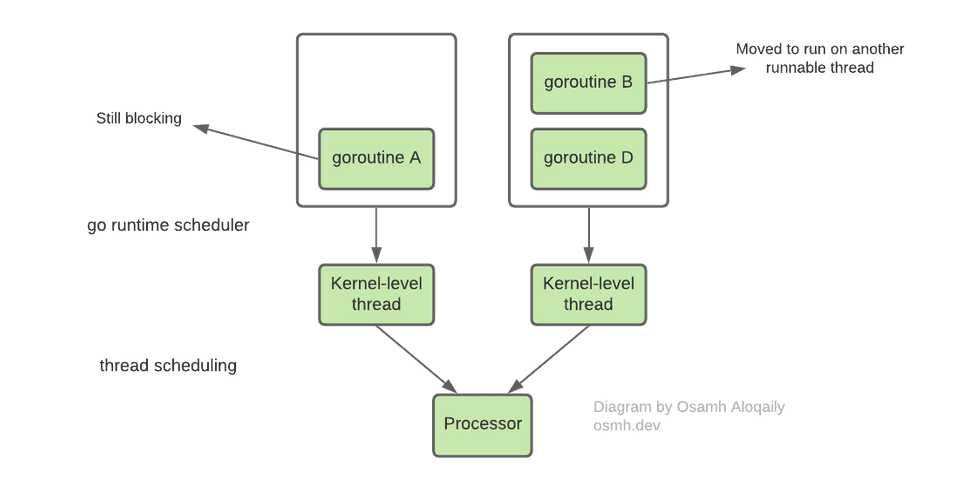

- Goroutine C has done executing.

- Go’s run-time scheduler by now would maybe realize, it would be a better idea to move goroutine B to another runnable thread and not just wait forever for goroutine A to finish.

- Goroutine D has now done executing.

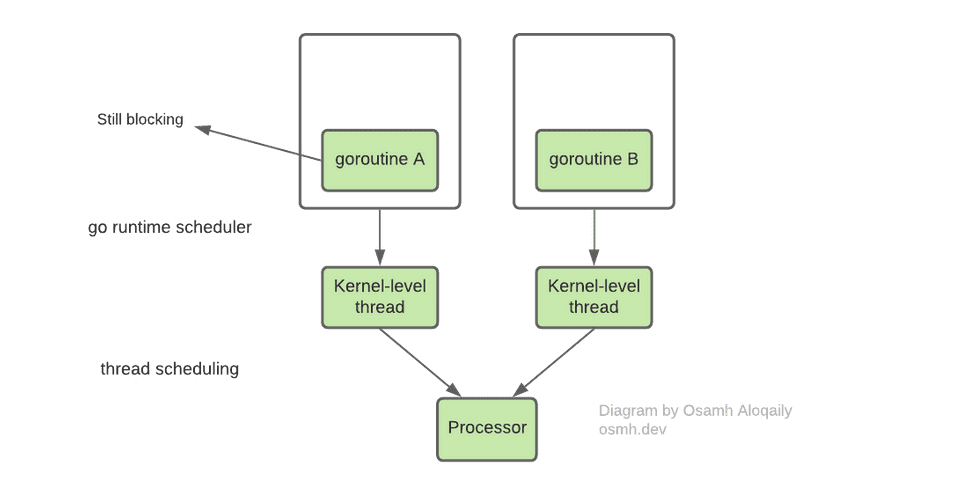

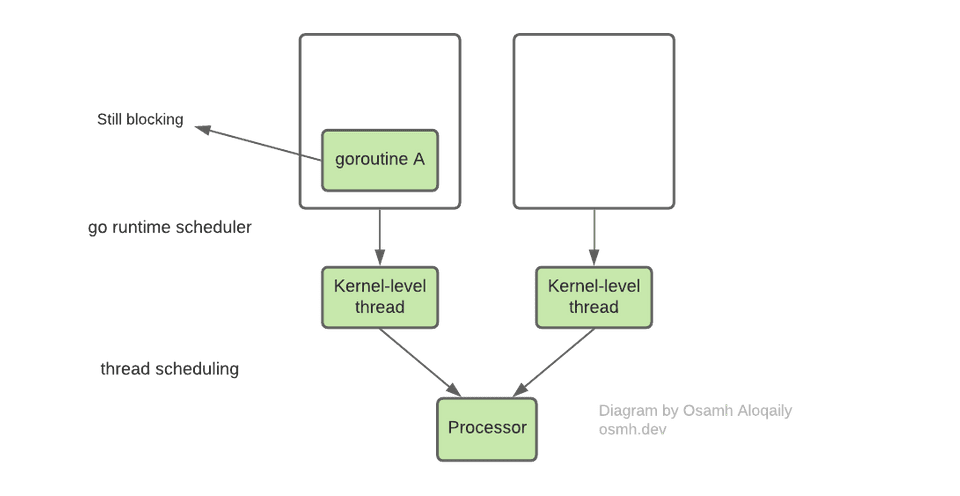

- Goroutine B is now also done, while the kernel thread on the left occupied by goroutine A is still blocking!

If the run-time scheduler never bothered about rescheduling blocked goroutines to another runnable threads, goroutine B wouldn’t have finished executing by now! Of course, this is a very simple example, but imagine this taking place on more complex and larger programs consisting of thousands of goroutines. The difference would be huge! The developer sees none of this, which is the point. goroutines can be very cheap: they have little overhead beyond the memory for the stack, which is just a few kilobytes.

One more thing, what about the size of stacks? Fortunately this is also managed for even better efficiency. Quoting an answer on go’s page of FAQ:

To make the stacks small, Go’s run-time uses resizable, bounded stacks. A newly minted goroutine is given a few kilobytes, which is almost always enough. When it isn’t, the run-time grows (and shrinks) the memory for storing the stack automatically, allowing many goroutines to live in a modest amount of memory. The CPU overhead averages about three cheap instructions per function call. It is practical to create hundreds of thousands of goroutines in the same address space. If goroutines were just threads, system resources would run out at a much smaller number.

Go channels are also used for facilitating the communication between goroutines, but I’m not going to focus on this for this article. If you’re interested, you can read about how channels work here

Conclusion

Goroutines is an inherent part of the language. They utilize a concept called coroutines. They are easy to use and can be very cheap performance-wise. Go run-time scheduler multiplexes goroutines onto threads and when a thread blocks, the run-time moves the blocked goroutines to another runnable kernel thread to achieve the highest efficiency possible. Go also provides many tools to support goroutines such as channels for communication between goroutines. If you were to develop an app or a service where concurrency is a concern, you should definitely consider using Go!